I’ve written previously about the gap between mainstream policy-making and systematic, knowledgeable use or understanding of behavioural science. And here I am again, suggesting that the wording of the Brexit referendum could have been smarter, and that the Leave campaign tapped into our cognitive biases much more effectively than did the Remain camp. So … was it cognitive bias wot won it?

The Wording

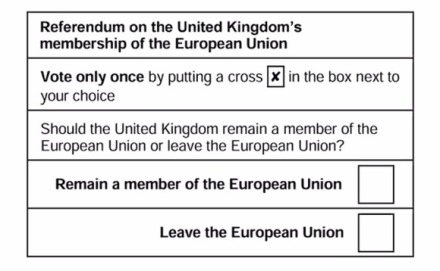

My interest from a behavioural perspective was first piqued back in September, when it was reported that the draft referendum wording had been changed. My instinct was to agree that the Yes/No question initially drafted (“Should the United Kingdom remain a member of the European Union?”) would indeed favour stay, due to status quo bias. But I was concerned about the agreed final version, which I felt had an inbuilt bias the other way. I tweeted this at the time, to – let’s be honest – very little interest:

My rationale is that if you were looking for a balanced choice, the key words would form a semantic pair. I think that, technically, we are talking here about complementary antonyms. On/off is an example. Stay/leave works, in my view. But Remain/Leave doesn’t; remain carries a higher cognitive load to process than does leave, as it is less idiomatic. Depart would be a better pair with Remain.

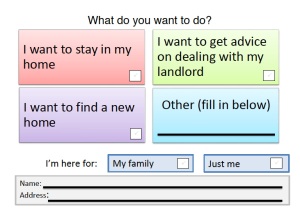

This matters because, when faced with a higher cognitive load, we process information less well. It’s why a lot of my work with local authorities includes an element of making sure that we use everyday language. We want people to make good decisions.

Is it a big deal, though? The more reflective a decision is, the more it relies on System Two thinking, so the less significant are the biases and heuristics of System One. And this decision, considered over many months, perhaps shouldn’t be influenced by something as seemingly ephemeral as the question wording. But, in the privacy of the polling booth, particularly if you enter it as a ‘don’t know’ …We’ll never know, because there is no control sample – and no voter would be aware of the effect influencing their decision.

Effects triggered by Leave campaign

“Vote Leave, Take Control” was very, very clever. Chris Dillow at Stumbling and Mumbling recently wrote on cognitive bias and politics and called it a ‘stroke of genius’. My rationale is different to his, which focused more on how people feel about inequality.

My thoughts refer particularly to the ‘Take Back Control‘ slogan, or, as shown here, ‘Taking Back Control From Brussels’.

I think two powerful behavioural effects are at work here. And I partly recognise them because I’ve used them – together – to great effect in my work. But before I explain, put yourself in this scenario:

Imagine calling a mobile phone company to cancel your contract. You might half-expect to be put through to a Retentions team who might offer you more texts or 100 extra minutes per month as an incentive to stay. With me so far? But what happens is that Retentions say, “Oh, look. There are 100 extra minutes per month on your account. What do you want me to do with them?”. Pause for a second and think about it. They’ve completely reframed your call: you now immediately understand that you have this thing, that you are at risk of losing. It wouldn’t work on everyone, but I’m pretty sure I’d be more likely to stick with my current provider if they tried this, than if they didn’t.

What this imaginary phone company and ‘Take Back Control’ have in common is combining Endowment effect and Loss Aversion. In a nutshell, endowment effect is the value I instinctively ascribe to something simply because it is mine. Coupled with the (more widely understood) loss aversion, whereby I acutely feel the potential loss of what is mine, this is a powerful combination. The expertise with endowment effect often lies in communicating very succinctly that there is something I have, that I may not have been aware of at the start of the sentence (or, in my phone contract example, at the start of the call). In Public Health, we are using endowment effect when we write to someone to say ‘Your NHS health check is due’ (my italics) which, all other things being equal, gets more people attending. So what is so clever about the use of endowment effect in the concept of ‘taking back control’? It is the way that a status quo ante is implied by the word ‘back’, a time when I had control. Further, it is very hard to contradict once it has been used; as they didn’t reframe with an alternative, vivid understanding of what it was to be ‘in control’, Remain were essentially saying “it’s OK to have lost control”.

Finally, think how much more effective ‘take back control’ is than ‘take control’. That, as Jonathan Flowers said to me when we were discussing this, sounds like hard work.

Leave’s missed opportunities

It’s not hard to make a case that the main flaw of the Remain campaign was in allowing the debate to be framed by the Leave camp. Framing isn’t a behavioural effect as such, but how something is framed provides the context for decision-making – and biases – to play. Taking just one example, the Leave side managed to get ‘freedom of movement’ spoken about as though it’s a one-way street. And this is still true; listen to news pieces even today about the issue, and it’s all about EU citizens’ right to move to the UK, not about UK citizens being able to live in any of 28 countries, as a result of being EU citizens.

How could the campaign have been run to reframe this? I’ll offer just one example: loss aversion is good to tap into. For UK citizens like me and my family, the Leave campaign was about removing our right to live in 27 of those 28 countries. Expressing it more vividly, they want to take 95% of my/your passport away. Leigh Caldwell, a fellow behavioural practitioner, wrote about this, evocatively and emotionally, before the vote. But I’m trying to be hard-nosed here, and I don’t think you have be a super-creative at Saatchi to imagine something visual and vivid to bring this home. I’m picturing something involving Mr Farage, a passport and pair of scissors. Alternatively, for the more nostalgic among you, how about a “No more Auf Wiedersehen Pet” message, with a picture of that nice Jimmy Naill?

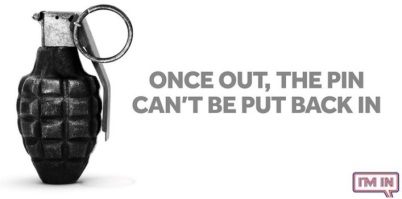

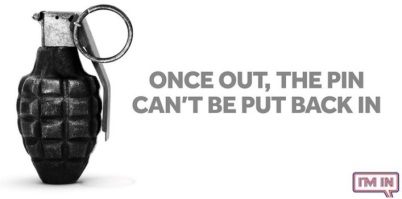

Clearly, some good ideas – that would have worked hard behaviourally – were around, but not acted on, as this article in Campaign makes clear. This draft poster, in particular, could have been expected to trigger status quo bias effectively:

So – was it cognitive bias wot won it?

I’m not saying that these were the issues that settled the vote – that with more self-awareness of our cognitive biases, the result would be different. We don’t know; there’s no control sample. But I do hope that people in the Remain campaign would now look back and inwardly facepalm.

Is it too late to reframe the debate and decisions?

Most, if not all, readers will have witnessed the emotional fallout from the Brexit vote, even if they did not feel it themselves; the sense of voicelessness and loss that has even led to the publication at short order of a new national weekly newspaper. It’s not clear what will happen now, as many authoritative voices advise us, so perhaps there is time for those who are in favour of the UK staying in the EU to move away from using purely economic language, and begin to talk about these issues in a way that recognises how we really make decisions.

Before I go …

One rider to all of this: friends have encouraged me to write down what I’ve been saying out loud recently, and here it is. I hope these things are worth saying, because the referendum did happen. Sure, it could have been done better. But my view, for what it’s worth, is that referendums are almost always the wrong thing to do; so no referendum at all is preferential to a behaviourally literate referendum. This 2010 post by Paul Evans is a good overview of why, though Noel Gallagher puts it more vividly.

Tell people who'd be interested: