This is about an award-winning project carried out by the Housing team at the London Borough of Ealing, supported by With The Grain (that’s me). We think we achieved a 70% reduction in the number of families being placed in temporary accommodation by the Council, and the main principles are now being scaled into the Council’s ‘business as usual’ approach. We think it has the potential to save millions and improve the wellbeing of hundreds of families. So, if you’re working out how to do Demand Management in practice, or wondering how to make the most of behavioural insights in local public services, you need to read this.

The approach we took was co-designed. Council staff were involved in developing ideas, drafting scripts and specifying content. Get in touch if you want to know more about how we did it.

Helping people take control

We did this by helping families who are likely to become homeless (typically due to eviction or a breakdown of an existing household), to take control of their situation: to look for a new home for themselves if they are able to, rather than being funnelled into Bed & Breakfast (B&B) and Temporary Accommodation (TA) to wait for the Council to find them a home. This matters, because the reality of living in TA and B&B is not good for families’ wellbeing. It is also expensive to provide at a time of unprecedented cuts in local government budgets.

Our approach

Our ‘Reframing First Contact’ pilot consists of a conversation. We call it an advice session, with potential follow up phone calls and sometimes meetings.

We use a number of materials:

- a script for officers to use

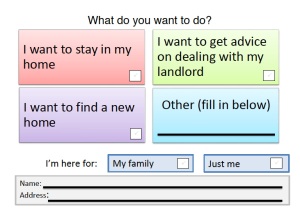

- a leaflet shown by Customer Services Advisors to callers, to help residents frame the conversation. This helps identify people who are eligible for the pilot

- a tablet computer with a front page of hyperlinks to the most useful sites/pages when searching for a home

- an action plan for residents to take away.

I’ll explain the process, so you can see how the materials are used:

- Resident arrives at Customer Services front door and is given a ticket for housing advice

- When called, the housing Advisor makes eye contact and shows them the framing leaflet, to immediately establish whether they meet the criteria set out:

- they say they risk becoming homeless

- they have dependent children

- they indicate that they do – or might – need to find a new home

- If the Advisor judges (usually within a minute) that someone is eligible, the Advisor calls a pilot officer and asks them to help the residents as part of “our new service”

- The officer collects the resident, and takes them to a room where they sit alongside the resident. When they can, they give the resident the best chair, to help them feel ‘in control’

Photo posed by officers

- They then have a conversation based on the agreed script, with a tablet computer available – so they can search for homes and other information

- We don’t collect any personal data, except contact information. We found collecting personal data tended to steer conversations away from residents’ capabilities, and also enforced an unequal power balance between the expert/gatekeeper officer and inexpert resident.

Behavioural Effects we used

Throughout, our intention has always been to present it as normal for people to look for their own home – one that they can afford – and then to make doing so as easy as we can. To achieve this, we used around twenty identifiable heuristics, including the ones listed below. We also stopped the inadvertent use of effects that were having an adverse impact on behaviour.

- People are primed to frame the conversation. The What Do You Want To Do? framing leaflet tests that the resident is comfortable saying they are someone who needs to find a home, as distinct from being given one. (The business as usual – BAU – approach is to assume that someone wants to be a ‘homeless applicant’ – and therefore a customer.)

- Scarcity effect – when the Customer Services Advisor calls the pilot officer, she says: “I know the new service is really busy, but it would be great if you could squeeze in Mr A right now”.

- Talking about looking for a home, we set the default as ‘looking for yourself’

- We increase salience by referring to a time-limit. “This is about finding the home where you’ll be tucking up the kids at the end of next month”

- We have an emotional ‘reward’ in mind – settling down and being happy – and we talk about a ‘home’ (whereas the BAU approach is to refer to a ‘property’)

- We make social proof available – to demonstrate that others like have done this and are happy

- We reduce cognitive load – avoiding jargon and unnecessary concepts (of which there are many in the BAU approach)

- We avoid endowment, like “duty” and “entitlement” (which anchor the conversation unhelpfully in the BAU approach)

- We avoid scarcity effect when it’s unhelpful, like telling people how tough it is to get a council home. (In the BAU approach, this was seen as “managing people’s expectations”; however, Prospect Theory predicts that this encourages risk-taking behaviour).

- We have a commitment device – an Action Plan – so that residents can note the websites, agents, etc they will contact

- We increase the salience of, and of plans and information by asking people to write them down themselves

- We help people visualise their plans – asking them to explain where and when they are going to search – so they’re more likely to do them

- Reciprocation – “when you find somewhere, we will be able to help you with the deposit”

What did we find out?

We think the approach we took, and the way it worked, showed three main things:

- Co-production works for behavioural techniques. Drawing from a wide range of behavioural effects, council officers worked alongside a behavioural practitioner to create a new approach. It’s their project.

- Using behavioural insights, we can increase demand for an ‘upstream’ service that supports independence and self-sufficiency, and so reduce demand ‘downstream’ for services that are expensive to provide, may not improve wellbeing and may increase dependency.

- Local services can use behavioural insights at an operational level. It doesn’t depend on developing or changing local policy. This work has been commissioned and sponsored by a Director and service heads.

What was the impact?

We didn’t have enough control over the front door of Customer Services to set up a randomised control trial. However, we think the two main measures we do have are pretty conclusive:

- First, a qualitative measure at the end of the advice session, asking the resident if they plan to look for a home themselves (and whether they will look further afield if they cannot find somewhere local they can afford). Over a four month period from November 2014 to February 2015, the vast majority of residents who took part agreed to look for a home themselves (31 out of 34), including 21 who explicitly agreed to look for somewhere they could afford even if it wasn’t in the area they were living.

- Second, a hard Demand Management measure. Officers checked whether residents who take part in the advice session went on to become a ‘homeless applicant’ by cross-checking with application records. Just 2 of the 34 became homeless applicants, far fewer than would normally be the case.

How does this compare with Business As Usual? During the same period as the pilot, Ealing Council accepted 234 other families as homeless . These families did not benefit from the behavioural pilot service. This table compares the outcomes.

| November 2014 to February 2014 | Behavioural Pilot | Normal (BAU) method |

| Number of approaches about potential homelessness | 34 | 1127 |

| Number of homeless applications taken and accepted (leading to B&B/TA) | 2 | 234 |

| Acceptances as %age of approaches | 6%* | 21% |

*NB small base

These results suggest that our behavioural approach has the potential to reduce demand – in the form of provision of B&B & TA to families designated as homeless – by up to 70%.

Why this matters

When families are helped to find their own homes, in areas of their choice, that they can afford, they are able to settle down and begin to re-establish the family life that households in B&B/TA often find difficult to sustain. For more on the impact on families of homelessness and living in B&B and Temporary Accommodation, see Shelter and this report on the impact of temporary accommodation on health.

There is another driver of course. Like most of my work, this is about Demand Management. The London Borough of Ealing has faced severe cuts of £96m over a four-year period. However, demand for homelessness services is rising – due to a vanishingly small supply of social housing, and rising evictions in the private rented sector. So reducing the number of families in temporary accommodation is vital to reducing the cost of this multi-million pound service.

Our behavioural pilot points to significant savings, more practical to measure than an increase in wellbeing. Accommodating a family of 1 adult and 3 children in London for a year typically costs the Council between £18,000 and £27,000 plus officer time. So the potential saving to the Council, if it is able to assist at least 100 families to find their own homes, is £1,800,000. No wonder the Council is working out how to scale up the approach.

Award-winning

We’re proud that our project won the Grand Prix at the inaugural Nudge Awards, ahead of projects from the world of advertising and finance. My thanks to everyone at Ealing who played such a big part, and to Professor Richard Thaler for choosing a local government project as the Grand Prix winner. Those of us who work in and with #localgov know that it’s rarely seen as glamorous, but it makes a positive difference to the lives of millions. And, right now, we need to ramp up the use of behavioural analysis and insights to deal with the reality of major budget cuts.